The game no one wants to play

Our understanding of humanity is far from a complete picture. However, there are theories that have been strengthening their position in the worldview marketplace for many years. In this essay, we look through the lenses of these theories to answer the question “What makes us more human?”

The first set of lenses comes from Darwin’s theory of evolution. Humanity’s position at the top of the food chain is the result of three evolutionary forces: variation, inheritance, and natural selection. Diversity competes for limited resources; individuals best suited to survive reproduce more, spreading their traits through the population1.

On top of that, we place Donald Hoffman’s Interface Theory of Perception. To increase their chances of survival in harsh environments, organisms aggressively optimize energy expenditure. Whenever they can optimize something, they do. They simplify their senses and cognitive capabilities to levels that ensure survival with just a slight advantage over others. Senses that do not increase the chances of survival and procreation are lost, while those that increase the so-called “fitness” payoff are reinforced.

That is why humans cannot see infrared or ultraviolet light, hear below 20 Hz or above 20 kHz, or perceive gravitational or ionizing-radiation fields. We do not see atoms; instead, we see solid objects because that’s what helps us navigate the world effectively.

On the other hand, rotten food disgusts us, we fear spiders and snakes, and we crave sweet and fatty foods. We unconsciously clap when others clap and judge beauty in a heartbeat yet struggle to explain why.

For most of our lives, we run on the autopilot of evolutionary drives that help us quickly and effortlessly make decisions with limited information. We feel fear or disgust to avoid danger, or joy to encourage us to pursue beneficial opportunities like acquiring resources or procreation. In moments of intense emotion, we behave more like animals, reacting instinctively rather than thoughtfully.

But that’s how evolution, over millions of iterations, has pushed Homo sapiens to the top of the food chain.

Evolutionary Survival Mechanism

History shows us that humans have survived by forming tight-knit tribes2. This sense of belonging fosters loyalty and cooperation within the group but also encourages hostility toward those outside it34. In extreme situations, this can lead to dehumanizing opponents, making it easier to justify violence and oppression. We can see this in acts of cruelty, like the Ottoman Turks’ massacre of the Armenians (1915–1917, ~1.5 million killed); the WWII Holocaust (6 million Jews), the Rwandan genocide (1994, ~1 million in 100 days), and the Cambodian genocide (1975–1979, 1.5–2 million deaths)5.

Our brains are wired to make quick, often oversimplified judgments to conserve energy and protect us in dangerous situations. When we’re under pressure, this “monkey brain” makes us default to black-and-white thinking, scapegoating, and authoritarianism as a way to regain control and certainty67.

Our ancestors lived in environments where resources were scarce, and the brain adapted to see the world in terms of winners and losers. It taps into a primitive, zero-sum mentality: “If they gain, we lose.”8 This scarcity mindset can lead to the justification of extreme measures to protect resources or power, which historically fueled regimes like the Nazis.

The only reason we’re not acting like Nazi monkeys fighting for dominance is that we’re not in life-or-death situations. We’re also layering harmony and etiquette on top of these instincts. We don’t see this behavior unless we’re in a survival situation9.

Full Reality = Death, Part of Reality = Survival

Seeing objective reality could hinder the survival of the species because the amount of information to process would consume the vast majority of energy that could be better utilized in adversarial environments1. If we didn’t have the subjective perspective we would be spinning in a constant state of “I don’t know”.

Nevertheless, evolution promotes cognitive diversity, and therefore cognitive/personality types emerged within our population to increase the chances of survival in changing environments. So, not only can we not see objective reality, but the subjective dose is also perceived differently by each individual. Jung’s typology10 explores the differences in how individuals perceive, process, and interact with the world. Everyone is equipped with a set of natural strengths and immutabilities, which come at the expense of weaknesses and delusions in other areas. For instance, the Objective Personality framework defines two broad types of individuals:

- Double Observers (Single Deciders) have natural strengths in working out facts with understanding and control with chaos. However, this comes at the cost of delusions in seeing self and other people’s perspectives. They feel stuck in judgments and decisions involving both emotions and reasons. They have an all-or-nothing mentality when it comes to seeing positives and negatives in themselves and others.

- Double Deciders (Single Observers) have natural strengths in working out people problems, seeing both self and others’ perspectives, managing bad feelings, fairness, and decisions. However, this comes at the cost of delusions in resolving contradictions with facts and abstract patterns, new and old information, details, and categories. They have an all-or-nothing mentality when it comes to control and chaos.

Cognitive diversity has many efficiency, survival, and problem-solving advantages. Collective cooperation expands individual subjective limitations, creating a superior collective being. On the other hand, differences can cause conflicts when individuals try to impose their subjective and preferred ways onto others. Conflicts escalate to wars, especially when control, power and ideology are involved, and one group tries to impose “their way” onto others.

For example, Single Deciders often push for fairness, social democracy, and communitarianism to prevent selfish narcissists from exploiting resources, while their counterparts rebel by advocating libertarianism and individualism to avoid mass control. Similarly, Single Observers impose conservatism and traditionalism, seeking control and order, while their counterparts push for liberalism and progressivism, emphasizing diversity and freedom.

At times when the purpose of life was to compete, dominate, procreate, go to war, and die, these primitive mind programs worked well, promoting the spread of the species. Now, in times of peace, freedom, and longevity, we are left with vehicles that run on legacy programs. Although there is no easy way to update the vehicle, the way to become a better driver is through…

Hero’s Journey

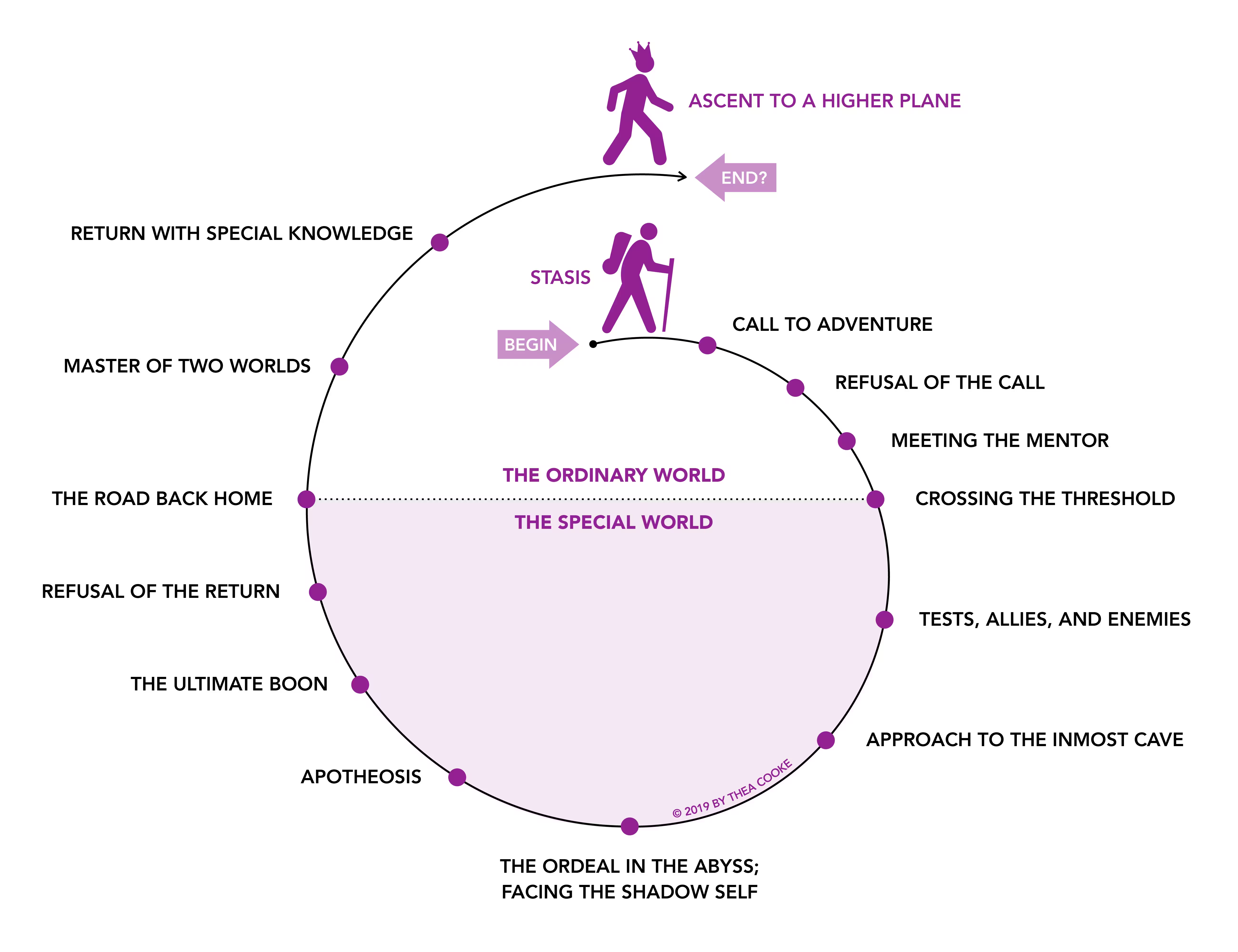

Joseph Campbell spent his life researching different mythologies from around the world. He found that they all follow a similar pattern, which he called the “hero’s journey”1112. The hero’s journey is a cross-cultural pattern in which a protagonist leaves the normal world, ventures into the unknown, faces challenges, undergoes transformation, and returns enlightened.

Objective Personality posits that people of the same types go through the same Hero’s Journey. They overdo their default programs (saviors) and leave a huge void in the opposite (demons). This one-sidedness puts pressure on the external environment, causing problems. When the problems get big enough (depression, health problems, relationship breakdowns, leaving religion, going broke) and the person can no longer avoid confrontation through coping mechanisms or push it into the unconscious, they are cornered and have no choice but to give up their default savior programs to finally “wake up” from their loop.

As a person progresses through their Hero’s Journey, they grow and mature, becoming increasingly adept at balancing these dual forces. Continuing the driver’s metaphor, the hero’s journey teaches us how to maneuver through life by effectively using the accelerator and brake pedals13. Rather than choosing sides, they learn to put one foot in control and the other in chaos, one foot in the self and the other in the group. This balance enables the driver to achieve life’s objective goals effectively and gracefully.

Hero’s Journey on a Collective Level

Humans, as living organisms, are part of larger organisms: institutions, societies, nations, and civilizations. In their works, Oswald Spengler14, Arnold Toynbee15, William Strauss, and Neil Howe16 have observed that civilizations often experience cycles that closely mirror the Hero’s Journey: confronting existential crises, undergoing profound transformations, and emerging either revitalized or fundamentally changed. National narratives frequently reflect this journey, particularly during periods of nation-building or recovery from significant challenges. While this metaphorical framework is interpretive, it offers a powerful lens for understanding the rise, fall, and rebirth of nations and civilizations, making the Hero’s Journey a universal narrative that transcends individual experience. Perhaps the force that causes these fluctuations is what Carl Jung described as the Collective Unconscious.

- Single Decider Nations: Systems like patriarchy, communism, fascism, totalitarianism, or dictatorships (with any kind of king) focus on either the collective or individual will, often at the expense of the other.

- Single Observer Nations: Systems dominated by religion or traditional wisdom and folk culture may focus on preserving established beliefs or practices, often resisting new information or change. Extreme progressivism, on the other hand, “throws the baby out with the bathwater” and wipes out all cultural legacy, including cultural achievements that unite society.

Double Deciding on a Collective Level

Double deciding at the national level is a system that balances personal values (individual rights) with collective needs (the tribe’s welfare)—this is democracy. A thriving democracy exists in the tension between seemingly opposing principles: self-interest and the common good, individual freedom and societal responsibility.

Democracies constantly refine themselves through debate, negotiation, and compromise. For instance, lawmakers and citizens navigate between personal desires for autonomy and the tribe’s need for order and fairness.

“Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried.”

~ Winston Churchill

The success of democratic systems lies in their ability to adapt and reconcile these tensions through constant dialogue and negotiation. A democracy, at its best, continually balances personal freedom with collective responsibility. The positive outcomes suggest that democracy is more aligned with fairness and justice.

Double Observing on a Collective Level

Double observing at the national level is a system that balances sensory (empirical) data with intuitive (theoretical) insights—this is science. Science thrives in the tension between seemingly opposing ideas: control and chaos, new and known, concrete and abstract.

The Scientific Revolution marked a shift from reliance on religious dogma to empirical observation and experimentation. Scientists like Galileo and Newton observed the natural world and developed theories that could be tested and revised.

“The opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.”

~ Niels Bohr

The success of the Scientific Revolution laid the foundation for modern science, which continuously refines its understanding of reality by balancing observation and theory, integrating the dual forces of concrete evidence and abstract reasoning. The positive outcomes suggest that science is more aligned with objective reality.

Civilization Progress with Addition of New Layers of Accountability to Objective Reality

The greatest civilization achievements occur when, in periods of the highest prosperity, individuals who hold control and power reflect on their corruptible nature. Instead of enforcing their will on others, they use their power to establish systems that prevent others and themselves from doing so, emancipating and fostering objective accountability. Examples include the system of checks and balances, separation of powers, the scientific method, democracy, the rule of law, the Abolition of Slavery, Universal Suffrage, and environmental agreements like the Paris Agreement.

The heroic act is rare but happens occasionally in the history of humankind, giving us hope for a brighter future.

The problem

Most of us appreciate the systems of law, democracy, science, and the technological advancements that have emerged from them.

We expect accountability and scrutiny from governments. We expect to be paid on time, for our insurance to be handled, for our employers to set tasks and goals. We take satisfaction in scrutinizing others—especially when they violate constitutions, standards, or rules we’ve agreed upon.

The problem is that accountability feels good only when it applies to “them.” As soon as we are asked to step into the cage ourselves, we panic. Our monkey brain rebels the moment we try to impose the same standards on our own lives.

We resist writing down rules, goals, and deadlines for ourselves. Most of us want to remain kings, not board members bound by shared authority. We surround ourselves with yes-men, blame external forces, and drift back into unconscious power saving autopilot.

“You either die a hero, or you live long enough to become the villain.”

~ The Dark Knight

THE GAME

The first step to play THE GAME is to admit that the source of our problems lies within ourselves. We must acknowledge defeat and helplessness before the fitness-optimizing forces of evolution.

- Everyone who wants to publish scientific papers eventually discovers that the problem is not the reviewer who rejected the paper, but the author who failed to meet the journal’s standards.

- Everyone who wants to run a business eventually discovers that the problem is not the market that doesn’t appreciate the product, but the unvalidated idea that created more problems than it solved.

- Everyone who wants to build a sustainable relationship eventually discovers that the problem is not the “toxic partner,” but the unhealed neediness that seeks validation for a fragile ego.

- Everyone who wants financial stability eventually discovers that the problem is not the economy or the tax system, but the budgeting and accountability they refuse to impose on themselves.

- Everyone who wants to create art eventually discovers that the problem is not a lack of inspiration, but the discipline of showing up to do the work even when uninspired.

- Everyone who wants personal growth eventually discovers that the problem is not the unfair world, but the refusal to confront their savior/demon loops and step outside unconscious autopilot.

Instead of trying to drive faster, we should choose roads with guardrails and build a safety cage for the vehicle we know we sometimes lose control of.

People who play THE GAME are found in environments that enforce objective accountability: disciplined business structures, the military and special forces, or recovery groups like AA and NA. These are places that work backward from what needs to be done—not from “what feels worthwhile according to my subjective, delusional self.”

Do you even play THE GAME?

-

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/41817484-the-case-against-reality ↩︎ ↩︎

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sapiens:_A_Brief_History_of_Humankind ↩︎

-

https://cooperative-individualism.org/toynbee-arnold_challenge-and-response-1934-1954.htm ↩︎

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strauss%E2%80%93Howe_generational_theory ↩︎